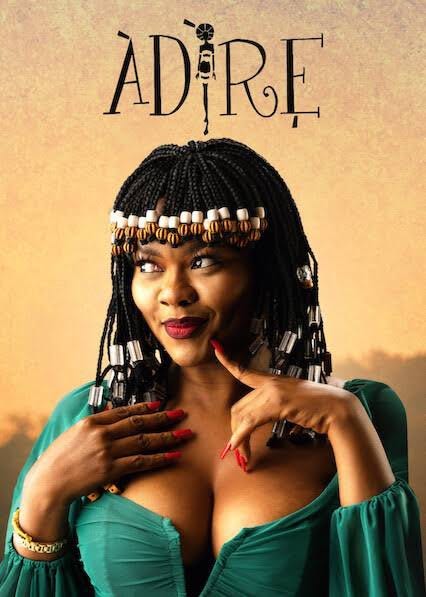

'Adire': Are Breasts Truly a Woman’s Weapon?

The film believes that the drive for infidelity on a man’s part is enabled by a change in his wife’s physical looks or her perceived neglect of them.

Sexuality has always been a tricky subject in Nollywood. Regardless of the relationship dynamic or the context, it seems as long as there is the subject of sex, the story is bound to be problematic. We’ve seen this in the way rape, sex work, and most especially, women’s sexuality have been portrayed.

Despite this knowledge, I still cringed when Adire, the titular character in Adeoluwa Owu’s Adire, referred to a woman’s breasts as her weapon, especially in the context of catering to men’s infidelity. Apparently, when men cheat, the fault must be from their women not utilizing their weapons, or getting too comfortable with their ‘old cargo’ appearance. This was cringy for me as I watched the scene where Adire implied this because not once has it ever occurred to me that a woman’s breasts, really her sensuality, could be the cure for her partner’s infidelity. The thought of that just didn’t sit well with me.

Adire follows the story of Asari (Kehinde Bankole) who returns to Oyo town and starts her life afresh after escaping her former life as a sex worker. Asari takes on a new name, Adire, at the dawn of her fresh start. However, she’d face opposition from women of the town, especially Sade, the holier-than-thou wife of the town’s pastor, as she becomes a magnet for their unruly husbands. Eventually, she warms her way into the women’s hearts by bolstering their sexuality and confidence which then drives their husbands back to them.

The film approaches the subject of sex and our society's relationship with it interestingly. First is the neglect of sexual education, especially in religious circles. The subject of sex is still considered a taboo while the open knowledge of an unmarried woman being sexually active is synonymous with promiscuity, and this is portrayed in how the women first perceive and relate with Adire. Also, Sade (Funlola Aofiyebi) as the strict, religious perfectionist Pastor’s wife, represents the standards that many overly religious people hold for others which blinds them to their own shortcomings. In a bid to maintain a chaste standard, she fails to educate her daughter sexually, who like most pastoral kids, learns outside the house. The devastating impact of Sade’s highhandedness is seen in her condemnation of the chorister who is pregnant outside of wedlock as she goes out of her way to make the young lady feel like an outcast. The film rightly makes a statement on how such a situation might be better handled through Mide’s (Femi Branch) reaction to their daughter, Simi’s (Tomi Ojo) revelation.

Still, a few things were problematic in the film’s portrayal of sexual relationships and the shared responsibility between men and women. First was Adire’s depiction as a sexually liberated woman who liberates the women of Oyo town and helps tighten their grips on their husbands who at first were flocking to her.

It’s not every day that the ‘source’ of a man’s distraction becomes his wife’s saving grace. Adire somehow finds a way to do this and even attempts to make it seem endearing in the most uncomfortable way. The scene where Adire and Salewa (Yvonne Jegede) meet for the first time is as confusing as it is slighting. The height of the cringe is when Adire replies to Salewa’s tears over her husband’s unfaithfulness by saying ‘That’s beautiful’. I want to believe she made an attempt at sarcasm with that line because I struggled to find the beauty in the man’s infidelity or his wife’s sadness over it.

Most of all, I struggled with the fact that the film believes and doubles down on the idea that the drive for infidelity on a man’s part is enabled by a change in his wife’s physical looks or her perceived neglect of them. This implies that the woman takes the blame for her husband’s unfaithfulness as she’s responsible for maintaining his attraction to her.

In the mix of this, somehow, I’m forced to wonder if men hold any form of agency, especially when Adire goes ‘A woman’s breasts are her weapons’ — implying that a woman must not only know how and when to use her weapons, she must strike so her husband is not lost to other women. It seems to me from this that women have a price to pay for their sexual liberation and that is pandering to men’s sexuality because men are horny and always so all the time. They hold no control over their sexual drive, and women need to cater to this god-given nature of men, especially once they are married to them.