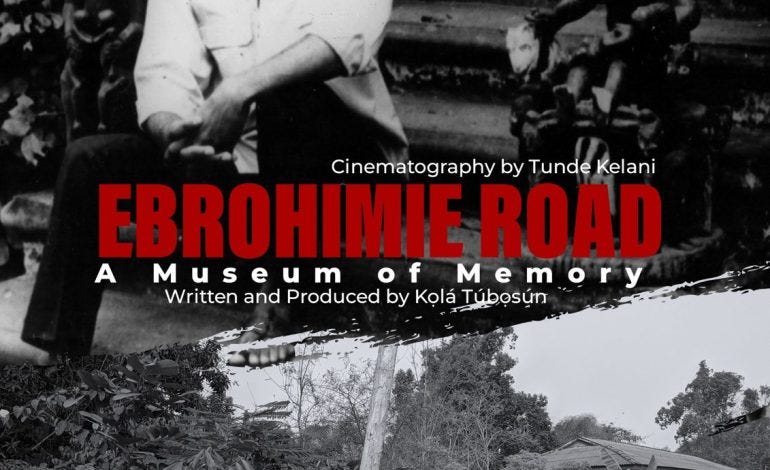

Capturing Wole Soyinka’s Legacy: A Journey Through Ebrohimie Road with Kola Tunbosun

In Ebrohimie Road, linguist, writer, and now filmmaker Kola Tunbosun embarks on a profound journey to preserve Nigeria’s cultural memory through the lens of Wole Soyinka’s early life at UI.

Memory is at the core of any society or people. The past is as important as the present and the future—more crucial for a better future. It is the responsibility of those in the present to ensure the preservation of memory and aspects of history that make us who we are as a people.

The Nigerian society struggles with the preservation of history. However, the important question is: do we know the severity of this problem? After all, when the value of something is not known, abuse is inevitable. Do we as a people know or even see the need for keeping a museum of our memories?

Linguist, writer, lexicographer, and now filmmaker, Kola Tunbosun, explores this thought extensively in his documentary Ebrohimie Road. He sheds light on the life of the first African Nobel Laureate, Wole Soyinka, and his time in the house he lived in during his tenure at the University of Ibadan. Ebrohimie Road—both the film and the house—is on its way to becoming a cultural sensation.

In this interview, Tunbosun speaks about the need for this story, our attitude toward memory as a people, and the experience of taking people back in time to view the life of the global prodigy, Wole Soyinka.

You are a linguist, your work as a translator, journalist and lexicographer has spanned decades.Now, you made a film. How does that feel?

It feels good. In the end it turns out filmmaking is just an extension of writing and documentation. I've mostly been in Linguistics for a while, but I've also been interested in any opportunities to tell stories, so I've done it by creating literary magazines,written poetry.

Now with the film, I was like, why not give it a try? I haven't done a film before, but I've watched films and I enjoy them. I also know what kind of things I want to see in a film. So it was an interesting challenge and I am happy with the results.

So a story on Wole Soyinka. Why did you want to tell it?

Well, there were a number of things that happened over different periods of time that pushed me in that direction. I knew I was going to write about that house because sometime in 2018, I started writing a book on Soyinka and that house was going to be a part of it. I knew that was where he lived when he taught in the University of Ibadan (UI).

It was also where he was arrested from and as such, it was an important character in his life story. I have a draft of the draft I wrote about it in my inbox and the book has not been finished.

Why did I think it was an important story? Just the number of connections that I found that related to the house — his arrest, his time in UI, fight with UI, and the toll that period took on his family and his personal life. He is a writer and a global icon but unfortunately, there haven’t been any stories about him as a human being, as an individual. I thought it would be nice to focus on that part, rather than just everything we already know about him.

What was your personal opinion of him as an artist and a person when you first encountered him?

I always knew of his work, but I can't remember when or how. In my generation, people who grew up in the 80s and 90s, Soyinka’s name was always there in your consciousness. Your parents talked about him when he was in the news. Especially in high school, during the nineties, from ’91 to ’97. Those are the regimes present in our imagination as someone who grew up in that era.

I met him for the first time in 2016 when I wrote about the building, Olaiya House in Lagos, which had been demolished by some criminal enterprise. He’d organized an event to talk to members of the family and stakeholders. I went there and introduced myself.

He’d read my story in The Guardian and we had a nice conversation. Then I scheduled another appointment to talk with him about a house that I had heard about, a bungalow in Lagos Island, Onikan, where his uncle had lived. I wanted to ask him some thoughts about it because the house had been pulled down as well and a high rise had been built there. He invited me to Freedom Park, we had a conversation and that was it.

Later, they declared one of his homes in the University of Ife where he used to live as a museum. I went to visit and I wrote a blog post about it. Anyway, I kept sending him emails about his life and other places he has lived in. Then, he invited me to his house in Abeokuta. I went and wrote a long piece about it.

I found out that he is quite accessible, quite different from the big man image you have of him because you've heard his name so many times. He is very easy going.

How did the film go from idea to having it on screen? What was that like?

The idea I had was for him to come back to that house and sit on the steps and retake the photo he took on the steps of the house. But the first time I talked to him about it, he said he wasn’t not interested in going back there. I tried to convince him, but every time I did, he told me the same thing.

The thought that he might say he didn't want to talk to us again made me eventually decide to just take the interview, talk to him and see where we go from there. We had a list of a number of people. Some of them died before we even got to the shooting, like Jimi Solanke, who we wanted to talk to. He fell sick the week we were supposed to interview him and died shortly after.

We kept running around to get a number of people to talk. Some people didn't know what I was trying to do. Some were curious about why I was interested in a house because it was just a house in a university and not important. Thankfully, I eventually had conversations with them and each conversation gave me something new too.

What limits did you have to embrace while making this documentary, like maybe materials you wish you had your hands on, or people you wished you could talk to?

The thought at the back of my mind was that I was running against time because this film was kind of late, because there are so many people in the country who don't know about the building or the relevance. Even Soyinka himself, as I found out, had forgotten that that was where he took that photo. So, it occurred to me that there were so many people we could’ve caught that would’ve probably given us better perspectives to the story who are no longer around.

For example, Professor Ayo Bamgbose, who was one of the members of the committee that denied Soyinka his professorship is still in UI. He is very old and frail.

A core theme of the film is memory, it's even in the title – Museum of Memory – what are your thoughts on our attitude towards our memory as a people?

Actually, when I look back on the work I've done over the years, I realize that I've actually been engaging with this subject all my career. The reason I had the dictionary of Yoruba names was to prevent memory from being lost, to allow people to put things they have in their minds in a place where other people can access when they’re no longer around.

When I used to blog actively, this was the same reason I go to all the places I visited and put them in a form where people can access. It’s the same reason I engage in translation and all that.

I think for the most part, we haven't taken memory as seriously as we should. Not just on an individual level, even on a societal level. The country hasn't put as much money and resources into preserving important historical spaces. There’s this book ‘An African Abroad’ published in 2022. It's a very famous, important document of literary travel history but I realized it’s been out of print for so many years and nobody knew where it was and we had to bring it back and republish it.

There are so many different opportunities that when you're having conversations with people, you realize that there's a gap in the memory and that the resources that could have answered these questions have been lost to history or somebody has locked it up in some place. For example, the Nigerian National Library, which should have preserved many of these years in films, books and journals have not done enough because they don't have the funds so people have mismanaged them.

I was at the British library in 2019 and I realized that literally almost any book that's been published in Nigeria, you could find it there. At least one copy in good condition of the original print is there. In Nigeria, I tried to find the same but I couldn't find anything. You probably won't find books published even in 1970 in a Nigerian library. So, we haven't done enough at all.

I don't even think we know the value of these things are important in nation building, because if you don't know where you have been, you don't know where you're going. This is what other people figured out a long time ago. When you walk through the city of London, you will see signs on buildings that say, for example, Isaac Newton used to live here or something similar. Buildings are preserved, houses are preserved, books, history is written, and published. More importantly, the government is putting money into the preservation of every book that has been published.

In Nigeria, you're supposed to send five books to a national library before you start selling. This is a law. You’d ordinarily assume that these five books will be distributed with one at the National Library in Abuja, others at the similar places in UI, Enugu, and Kaduna respectively.

They're supposed to be distributed around the country and anytime at any point in history, you're supposed to be able to go to any of these libraries and find them. But you realize that they don't have the enforcement mechanism so many publishers don't even send these books or when they send them, the National Library doesn't have enough resources to preserve and keep these books in good condition. You go there and I want to buy a book that was published in 1960, and you can't find it because nobody has it.

There are a lot of issues in the Nigerian archival systems. You go to the National Archives and the materials there are in terrible condition. So, part of what I've been doing over time is invest in archival documentation.

As a young student, would you say that Ebrohimie Road itself had an impact on you?

I was a student from 2000 to 2005 and I hadn't connected it at all to any history of Soyinka. I knew he had lived in the University of Ibadan, but I didn't know where he lived exactly. I didn't know anything about it. I mean, it was one of those things where people wouldn't have some knowledge, some idea, nobody talked about it. The first time I heard about that house was in 2017 or 2018 when a friend of mine just mentioned that Soyinka took that photo in front of the house.

I didn’t agree at first until I went there and found it [the house]. I looked at the photo and compared it. That was when I realized that it was true.

I never had any reason to go to that house. My own realization is that if I, who had spent five years in the University, didn’t know about the house, then there are many more people who don't know and who should know it.

The cinematography stands out for me. What informed your decision to work with filmmaker Tunde Kelani?

As you can tell, Tunde Kelani is a great Nigerian filmmaker, and I had worked with him in different ways before now. Not in this form or scale but I knew him and had a relationship with him already. When I got the news that I will get the funding for the film, he was one of the people I thought about as somebody who could be interested, but I didn't know whether he had the time.

I didn't know if he was free or if he would be interested at all. I was with a friend, another friend of mine in his office who told him that I was looking for someone to do cinematography and asked if he thought that no he might be interested. I told him the story and he immediately agreed to do it.

He was really eager as soon as I mentioned. I explained the rationale behind the film, why I thought the house was important. Initially, I thought he would be hard to convince because in my own imagination of the film, the house was the main character, which is why I named the film Ebrohimie Road.

Soyinka came and left, so it’s not just about Soyinka, it's about the house and any other thing that follows. He understood it from the beginning and was onboard. I think it was the same day or the day after we went to visit Soyinka himself. That was when I pitched the idea to him of going back to the house and he refused but decided to sit down for an interview instead. It was easy and I was not in doubt about his capability.

What was the process of securing the funding and how did it help with the production?

We got funding from Open Society and Sterling Bank, Nigeria. That made everything easy. That's all I can say about that.

Was there an unexpected discovery you made on this journey yourself?

Yes. I didn't know that Soyinka’s family remained in the house. I thought when he left, everybody left, and that was the end of that place. I discovered much later that the wife had lived there and with the kids. I also didn't know that the marriage didn't end when he left.

I realized that actually the marriage, of course, broke down gradually and they divorced much later. But when he left for exile, they were still together and the family actually went to visit him in Ghana and in, I think the UK, France or whatever, he was in a number of places and they went to visit him. The relationship continued over many years before they eventually divorced.

Also, I found out more details about his resignation from UI. I had some idea that he was frustrated but I didn't know why. I asked him and he gave us his own reason. I also asked his colleagues in UI who had actually done some research and found archival materials where they found what people said at the time, why they said what they said and all of that.

This film has screened in Nigeria and in some film festivals outside Nigeria. What has been the reaction of people so far and the most interesting you've gotten?

People seem to have enjoyed it. Mrs. Soyinka was one of the people I was interested in seeing how she reacted to it because it took us forever to get her to agree to come.

Why do you think she was reticent?

I think it's a memory of the time. I also think because for the Soyinka family members, people generally always ask them silly questions all the time. Sometimes, they answer the questions and then people use the answers for clicks and sensational purposes. I think that was why she was kind of worried and probably wondered what we wanted with our camera and if we wanted to ask about personal information.

We tried in any case, but our intention was not all of those things. My intention was just the memory of the house and it was helpful that I had interviewed the sisters and the children before I went to the mother. She was still reticent for a long time but she eventually agreed and she loved it. She was at the screening at the Institute of African Studies on July 11th. They had a Q and A with Tunde Kelani and she really enjoyed it. They even sang for her and all that. She sent messages back that she really enjoyed it.

The next day there was a screening on Ebrohimie road in front of the house itself. There were so many people, students from everywhere. People went to the steps and took pictures. According to the man who lives there now, Professor Fashina, people come almost every day to take pictures in front of the house. That made me happy. Everybody else seems to have had positive, mostly positive reactions too.

What are the plans for accessibility for more people to see it?

One of the things I'm hoping for is that eventually, we'll be able to see it on Netflix or YouTube or Prime or any of those places. The reason we haven't got there yet is because there were some scenes that I was still trying to cut or edit. There are a few more things that I need to fix on the film for it to be more accessible.

What impact do you desire for this film?

One, I'm hoping more people will see and enjoy it. As a filmmaker, I'm sure the most important thing is for people to see a film and enjoy it and leave with a very positive feeling. What you'll notice in the later part of the film is the advocacy for the preservation of spaces. Not just for Ebrohimie Road itself, which of course is important.

UI was trying to remove the building and put something else there. Hopefully, this film stops that idea.