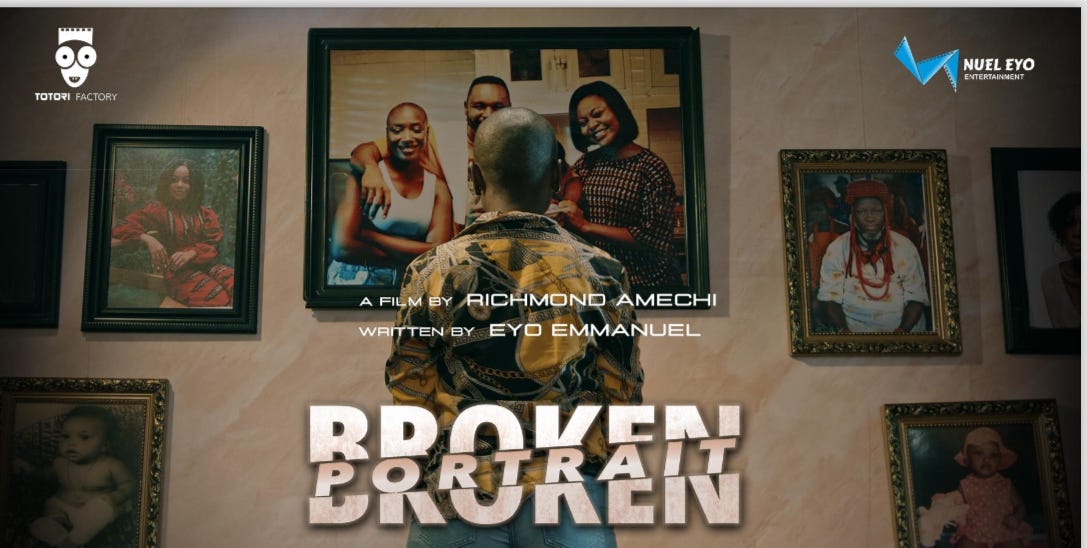

Confronting Biases: Eyo Emmanuel on Addiction and Family in Broken Portrait

In this interview, Nigerian filmmaker Eyo Emmanuel reflects on his debut feature film Broken Portrait, a powerful story that tackles addiction within the dynamics of a Nigerian family.

Every filmmaker has a story about creating their debut film. For some, it's smooth and exciting; for others, it's challenging. Regardless, telling these stories is something many filmmakers relish.

While Eyo Emmanuel isn’t new to the Nigerian film industry, he and his producing partner, Richmond Amechi, took a significant leap with their first feature film, Broken Portrait.

Directed by Amechi and written by Emmanuel, Broken Portrait explores addiction within the context of an average Nigerian family, using the relatable lens of romantic love.

In this interview, Eyo Emmanuel discusses the journey of making the film and the profound discoveries that led him to confront his biases, mirroring the Nigerian society’s attitudes toward addiction.

What made you choose family as the backdrop for this story?

My producing partner, Richmond Amechi, and I knew we wanted to make a film, but every idea I had was either too expensive or didn’t feel right for my first feature. One day, I was on a walk, listening to a podcast where people write in to share their situations. Someone said, “I wish my brother would just die.” When I heard that line, I instantly knew that was my story. She was talking about her brother’s drug addiction and how much money they spent managing it. I didn’t know her full story, but I felt I had found my story, so I started researching.

I realized that addiction stories often focus on the addicts but rarely on family members who struggle alongside them. Addiction doesn’t exist in isolation; it affects friends and family. I spoke to a recovering addict, sober for nearly a year, who shared his experience and how his family’s support was a constant push-and-pull struggle. In Broken Portrait, the main character isn’t the addict but his older sister, showing how his addiction affects her life and relationships.

When I sent the script to Richmond, he shared that his friend’s brother, also an addict, had relapsed. This coincidence confirmed we were on the right path. Our actors connected with the story as well. When our male lead, Taye Arimoro, read the script, he said the scenario was familiar because he had a friend deeply into drugs, and his family would call Taye to talk to him. It felt personal for all of us.

What are your thoughts on the belief that addiction is a disease?

My research opened my eyes to a lot, and I had to confront my own biases about addiction. Nigeria can be very judgmental; people treat addicts as if they’re no longer human. Right before I started working on this project, a school friend of mine died. Initially, we were told he was sick, but later, we learned he’d overdosed. The family preferred the illness narrative to avoid the shame associated with addiction.

People often don’t realize that addiction takes many forms—not just drugs but also gambling, sex, or even lying. Drug addiction, though, is the most criminalized. Addiction can be a disease in certain cases. I learned that some people have addictive personalities due to their DNA, making them more prone to addiction. It’s complex, and while it doesn’t apply to everyone, addiction is very challenging. For opioid addiction, like the character in Broken Portrait, the drug creates a dependency that makes users feel like they can’t live without it.

A former addict told me that no one could convince him to stop. Even when his girlfriend gave him an ultimatum, he chose drugs over her. Breaking free requires tough love and determination. The stigma needs to decrease so that people can seek help without fear of judgment.

Do you think films should directly address serious issues, and should filmmakers be clear about their stance on heavy topics?

This is tricky. I’m not a fan of films that preach. Nothing turns me off more than a movie pushing an agenda in your face. If I wanted that, I’d watch a political campaign or an ad. In Broken Portrait, no one says, “Don’t do drugs.” I wanted the audience to see it without being told. When films push an agenda too strongly, they become preachy and lose nuance. However, if you create the world of your story well, the message will come through your characters.

I chose not to make the addict the main character but instead his sister, showing how her “firstborn syndrome” affects her. We also explore other dynamics: the addict is the middle child, who, in Nigerian culture, is often overlooked, yet here he becomes the family’s central focus, overshadowing the last-born. I told Gbubemi Ejeye, who plays Isoken, the last child, to think of her role as “the last born treated like a middle child.” This nuanced approach allowed us to present family and romantic relationships without preaching.

You focused on character-driven storytelling rather than aesthetics. How did you select the cast?

When I was writing, I told Richmond that the family matriarch had to be Ngozi Nwosu. Although she’s known for comedy, I saw her in this role. During the table read, she shared that a friend’s son struggles with addiction, mirroring the dynamic in the film. The family in Broken Portrait is Igbo and Edo because I wanted to show an intertribal family—a representation rarely seen in Nigerian films.

I had Teniola Aladese in mind for the older sister role after watching her interview where she talked about moving from producing to acting, which inspired her character’s backstory. Gbubemi Ejeye was Richmond’s suggestion for Isoken. I specifically wanted a dark-skinned actress to visually underscore her isolation, as everyone else in the family is light-skinned, reflecting the colorism often seen in Nigeria.

For Osaze, played by Floyd Igbo, I initially had another actor in mind who turned down the role. Belinda Yanga recommended Floyd, and Richmond, after speaking with him, felt he was the perfect fit. His commitment was evident from the moment he stepped on set.

Casting Taye Arimoro as Bassey was the hardest. We faced the common challenge of finding male leads in Nollywood. Taye wasn’t my first choice, but when my friend suggested him, I realized he was exactly what the role needed. Watching the cuts, I saw he brought depth to the character in ways I hadn’t anticipated.

What was the experience of making the film like for you?

We’re just wrapping up post-production, so I’m still in the process, but it’s been both rewarding and frustrating. This film taught me not to fear “no.” We faced countless rejections, but we kept going. Being first-time producers, we had to prove ourselves to raise funds. I had to wear many hats—even acting as the location driver when the transport company sent us the wrong vehicle.

The journey pushed me out of my comfort zone, and I’m grateful. Once you’re this far along, you can’t turn back, so you push through.

How have you evolved as a writer and filmmaker?

My confidence has grown, both in writing and in leadership. I wasn’t just the Executive Producer; I was also the Producer, so I had to lead. I learned to balance diplomacy with firmness and get the job done without being overly tough. I don’t believe in harsh leadership on set.

Technically, I learned that not everything you write will make it to the screen. Our first draft was 90 pages, but we cut it down to 74. I realized I didn’t want to waste resources on scenes that wouldn’t make the final cut. Now, when I write, I think more practically about scenes, locations, and whether certain actions are necessary.

What impact do you hope this film will have?

Commercially, I want Broken Portrait to do well, to reach a wide audience. For the actors, I hope this opens doors for them. Ngozi Nwosu is playing against type here, and I hope this role shows her versatility. Gbubemi Ejeye and Teniola Aladese are phenomenal, and Taye Arimoro has a unique understanding of the craft.

Beyond the commercial aspect, I hope people who have someone going through addiction see themselves in the film. Addiction is isolating, but this story shows it doesn’t happen in isolation. One of the film’s themes is love and its complexities, whether familial or romantic. Love isn’t always easy, but it endures. I hope audiences see this and that Broken Portrait starts conversations about addiction and love.