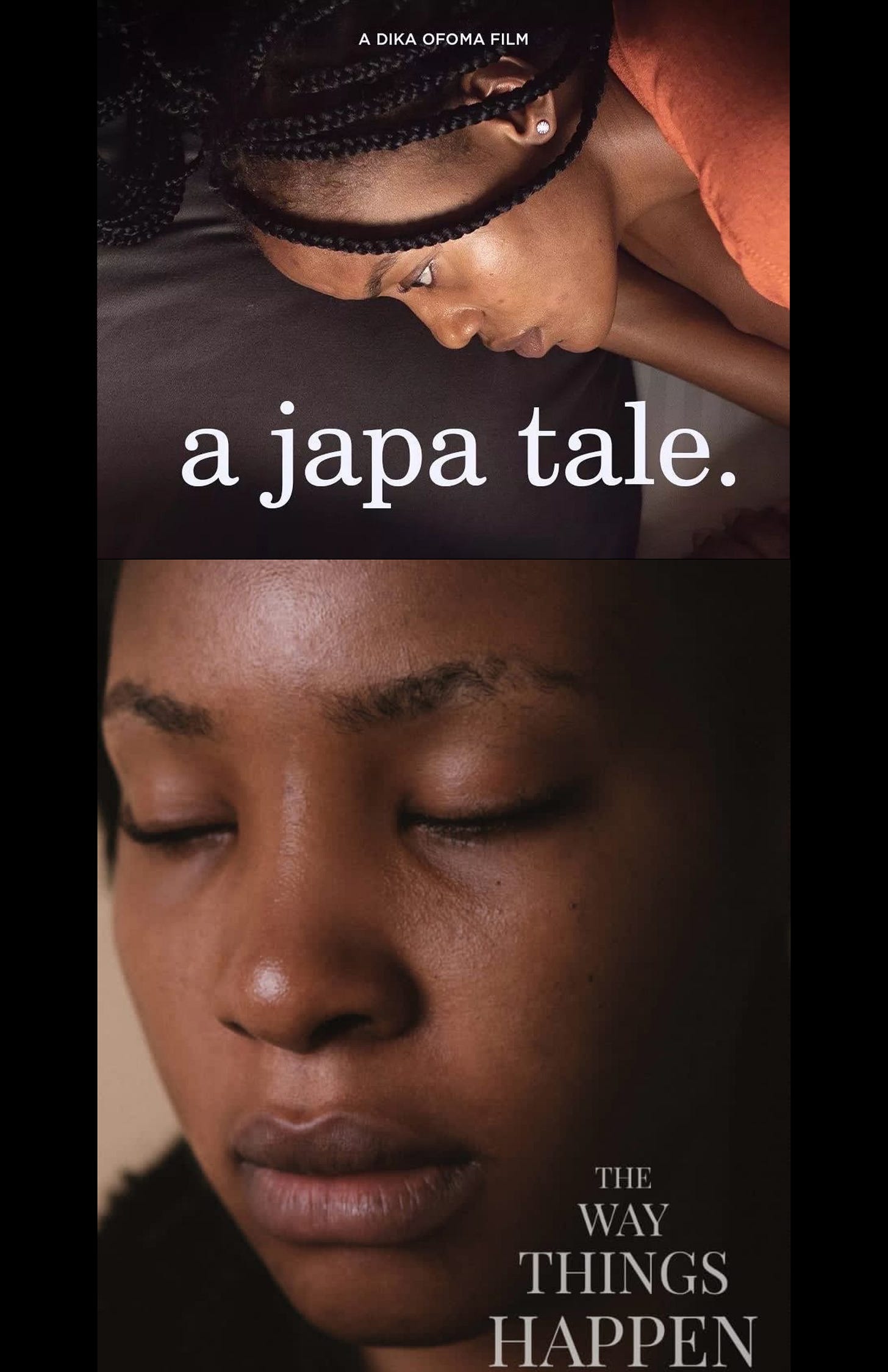

How Dika Ofoma Films Love and Grief.

Understanding Dika Ofoma's filmmaking approach through 'A Japa Tale' and 'The Way Things Happen'.

I recently saw Dika Ofoma’s A Japa Tale, released in January. It is a short film about a young couple on the verge of separation because the boyfriend plans to leave Nigeria. What struck me the most about the film is how Ofoma creates an intimate environment between his characters and viewers; it is as though he leaves you in a room to converse with the characters. Another thing that stands out is its unique use of silence in between dialogues which has as much meaning as its dialogues.

After seeing the film, I got curious about Ofoma’s approach to filmmaking and dug into another of his film, The Way Things Happen, which he co-directed with Ugochukwu Onuoha. Both films share many similarities. A Japa Tale follows a couple, Emuche and Dubem, trying to navigate their relationship after Emuche learns that her boyfriend will soon japa. The Way Things Happen, on the other hand, revolves around a young woman who has to come to terms with the death of her lover. In both films, the men are absconding into worlds beyond either by choice or by force.

They also have similar openings. In A Japa Tale, Ofoma opens with the couple in bed. They wake up, then goof around a little. We see a similar opening scene in the twenty-minute The Way Things Happen: the couple — Ikenna and his girlfriend — are in bed. Both openers are created with handheld shots, giving it a shaky cam effect. It is a technique used to create a semblance of a third party, the audience, in bed with the couples watching their display of affection. Ofoma indeed gets our attention by making us a third wheel, and he achieves this without fancy camera movements such as a tilt, pan or zoom. It is because he desires an intimate relationship with his audience: he doesn’t just want us to hear what the characters are saying. So, he uses the camera to inform us and make us see — and this is repeated across both films.

A mother is also present in both films, specifically, the boyfriend’s mother. In A Japa Tale, Dubem’s mother spends some minutes on screen. And annoyingly so — she complains that Emuche cannot cook, and later tells her that Dubem will leave the country no matter what. Though Ikenna’s mother is not seen on screen in The Way Things Happen, her voice is heard over the phone when she comforts her deceased son’s mourning girlfriend. When I noticed this in both films, I thought that perhaps this motherly presence simply gives insight into the relationship Ofoma has with his mother — she has a significant presence in his life, and he finds solace in her. “I think that was just my attempt to reflect our parents’ involvement in our lives,” Ofoma tells me.

The most significant similarity in these films is that they touch on separation. While the forms of separation differ, Ofoma does a fine job of making the audience understand the pain of losing a loved one. The separation in A Japa Tale comes in the form of migration or japa, as Nigerians have christened it. Daily, people leave the country in their numbers. Dika makes this quite intimate, as we see closely how migration affects those we love and leave behind.

The Way Things Happen deals with a different kind of separation — the separation from life itself. The theme of separation is highlighted by wide shots, which are intentionally sparse in Ofoma’s budding filmography, making them even more potent. At the end of A Japa Tale, a wide shot is used to capture the two lovers saying goodbye to one another. In The Way Things Happen, Ofoma employs the wide shot to amplify loneliness and grief when Ikenna’s girlfriend mourns him. We see Emuche alone in large spaces, away from the tight spaces she used to share with her lover.

"I’ve surely lost loved ones to death, and I have been separated from family and friends due to the japa wave. So, making these films was a way to share some of my personal experiences with loss and separation," Ofoma shares. The young filmmaker has spoken about separation several times on his social pages, and film is one medium he uses to engage and heal. “I spent most of last year mourning loved ones; writing and making this film was one of the ways I processed my grief,” he wrote on Twitter when the film was released. When asked why most of the effects of the separation are felt by the girlfriends in the film, Ofoma simply states that “it’s a coincidence”.

So far, Ofoma has shown us love on screen, and he has shown us pain too. “I draw from my personal experiences as much as I can,” he responds when I asked how much of himself is in the stories he tells and wants to tell. His style is evident in his two films, and I look forward to the future projects of the film journalist-turned-filmmaker. Although I would like to see him touch different themes entirely, I understand that he, like most artists, will always put elements of himself in his stories. Anyway, who am I to tell an artist which parts of himself to pour into his art or how much of himself is to be poured?