How Editi Effiong Made the Netflix Global Hit ‘The Black Book’

The Black Book is the biggest film in this era of Nollywood; here's how Editi Effiong made it.

During General Sani Abacha’s regime in the late 90s, a covert squad of highly-trained military men was assembled to target his regime’s opponents and critics. This group, known as the Abacha Strike Force and led by the infamous Major Hamza Al Mustapha, included Barnabas Jabila, popularly known as Sergeant Rogers. Legend has it that he was a man gifted with exceptional skills, quick reflexes and everything that made a soldier brilliant.

As the story goes, Sergeant Rogers could shoot a bird out of the sky, and as one of the standout members of this force, he was often assigned to various high-profile nefarious cases, leaving his mark on Nigeria’s history.

It is around the legends and actions of men like Sergeant Rogers that Editi Effiong crafted an audacious film that shines a light on Nigeria’s dark military past and its enduring impact on today’s politics. Like many filmmakers romanticising historical events, Effiong pondered how a small change could alter the course of history. He wondered what if, upon repentance, someone murdered the son of a man like Sergeant Rogers.

This concept served as one of the inspirations for Paul Edima, the central character in Effiong’s Netflix global hit The Black Book.

“On the other hand, I am in this industry where the police have been arresting young people and causing all kinds of damage, so this is a story we need to tell,” Effiongs told In Nollywood. “But, obviously, I knew that you can’t tell a story like {this] as is; you have to wrap it as a trojan.”

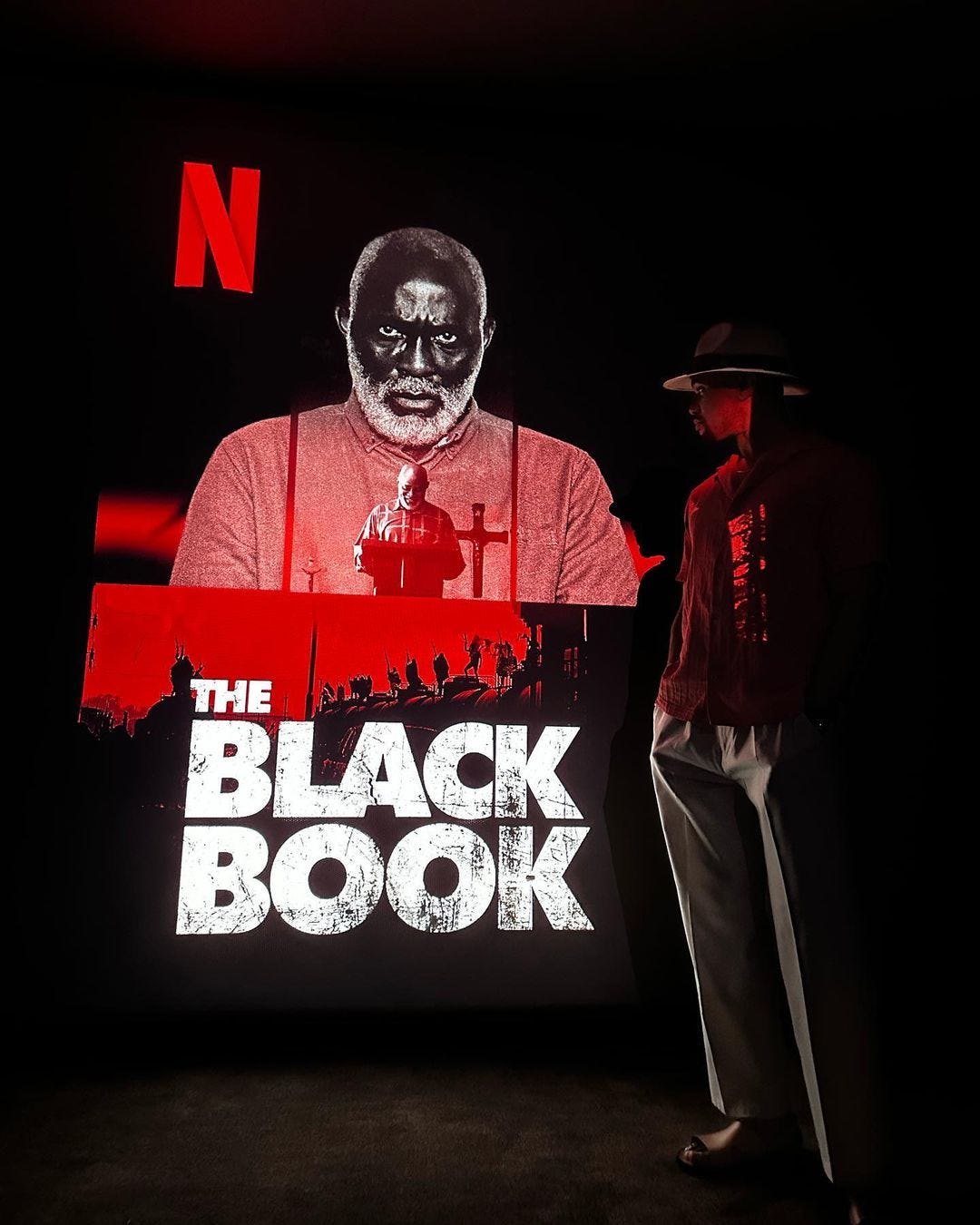

The Black Book is a sombre tribute to Nigeria that tracks the atrocities of the past and their reverberations in the present. Edima’s only son is killed by members of SAKS, a fictionalised version of the deadly police unit, SARS, as a replacement for an actual criminal. This act was orchestrated by individuals from Edima’s dangerous past, and to clear his son’s name, he travels the road he once sought redemption from.

It is a big, bold picture, and the scale of it is an achievement in Nollywood filmmaking. CNN described it as “Nollywood’s biggest film yet”. However, while much has been said of its scale and million-dollar budget, the bigger story behind the scenes is one of determination, relentlessness and audacious ambition.

Effiong and his team initially did not set out to make a big film.

“We didn’t go out there trying to make the biggest film, do the biggest logistics or build the biggest sets in Nollywood history,” Effiong explained. “I don't think my ego is that big; we were just trying to make a film and the film became what it is.”

The original idea was to shoot a thirty million naira film about a man chasing something from his past, but the more Effiong delved into The Black Book with his co-writer Bunmi Ajakaiye, it became apparent that the story possessed greater depth, a gem within a gem that needed more resources and time to flesh out fully. But Effiong always knew the film would be ambitious and difficult to pull off.

Financing “The Black Book”

Before the pandemic hit, the techpreneur turned filmmaker had set aside some funds for the project, but seeing that the story was looking bigger than earlier envisioned, he turned to his community of friends, mostly tech founders, some of whom he has known for years. He presented his vision to every single one of them, convincing each to come on board as an investor.

Some of them shared their reasons for backing the film during the #AfricaTechThisWeek's Twitter Spaces hosted by Fatu Ogwuche on Thursday, September 21, 2023.

Subomi Plumptre, an investor whose company, Volition Cap, has invested $250,000 in African films, explained, “I think for us, it was really just the passion and the person behind the movie; his antecedent precedes him. Editi has always been this crazy creative guy [who] can talk his way into any room.”

Kola Oyeneyin, a cofounder of Volition Cap, was particularly impressed by Effiong’s passion and persistence in convincing them to back this story.

“I think the first thing I want to highlight is Editi’s ability to just stay on,” Oyeneyin mentioned. “Just as he did with trying to convince RMD to be the star, the lead actor on this, it was the same way he literally got me to look at it.”

Throughout the production, Effiong made sure to keep his investors in the loop; it was important to him that they knew he valued their contribution and trust. Despite the gruelling and hectic shooting schedule, he provided them with weekly investor reports, complete with on-set photos and updates.

He explained, “We had committed to [doing that]. It's very important because I had to look at the big picture for the industry; the industry doesn't raise money as much because people don’t realise that this is a business. People give you money and want to see [working].”

Production Begins

After two years of writing and a year of intensive pre-production, which included location visits, multiple script drafts and discussions with the Nigeria Police and Armed Forces for permits, Effiong was prepared to make the film and was seeking a director.

No one was willing to commit to a single film for a year, which was what the film required, leaving him with no choice but to direct, as his feature debut, a film of monumental scale.

Unsurprisingly, he was scared. His only directing experience had been his terrific short film Fishbone and the pickup scenes he directed for Up North. He was also juggling far too many essential responsibilities on the project, and self-doubt was creeping in. “I didn’t have that full confidence of going to direct the thing,” Effiong admitted.

The ingenious solution was to surround himself with a technical crew with more experience, folks who could oppose him. Conversations were had with one cinematographer, and while they connected, Effiong felt something was missing.

“I needed someone who could challenge me, like absolutely challenge me,” he emphasised. “And the further I walked into what I wanted The Black Book to be, I needed it to be beyond reproach technically because the scale of the picture was such that if I made a mistake technically, I am dead.”

This led him to hire Yinka Edward as the film’s director of photography. They met and spoke for hours about filmmaking and life, and Effiong was captivated by the cinematographer’s knowledge and profound care for storytelling.

“I’d never spoken to someone in the industry who had that vision and dedication to quality like Yinka did. Yinka is exceptional. He is a terribly amazing artist; his commitment to story, not even picture, I had never met anyone like that in the industry who’s that committed,” he gushed.

Edward’s commitment extended beyond set. He oversaw the post-production and linked Effiong with the film’s editor, Antonio Rui Ribeiro, because “it is his work and he needed to see it look beautiful.”

His expertise, though, came at a high cost, and he had a process of doing things which was far too different from what happens on a Nollywood set. While Nollywood set-up time typically takes twenty minutes, Edward’s took an hour or two on average, which shocked and worried his director initially, but after they rolled the camera for the first scene, Effiong promised never to question setup time again.

Principal photography began in January 2021, and everything appeared to be proceeding smoothly until unexpected challenges started creeping up. First, they realised that they were burning through their budget quicker than anticipated, and the possibility of completing the shoot on schedule seemed uncertain. Then COVID struck, affecting key cast and crew members, forcing a two-week break which caused a massive hole in budget and meant an even tighter shooting schedule.

As if these challenges weren't enough, an important actor left the project during the shoot, necessitating alterations to the storyline. Effiong admitted that this development initially left him disheartened. However, he soon realised that this setback provided an opportunity to enhance the story. This habit of engineering solutions to problems was common throughout production.

Joshua Enakarhire, the film’s Assistant Director, told In Nollywood Effiong is a genius at fixing problems. “Editi has such a high level of resilience. I always saw him quenching fires as they came. So if a challenge comes up, he will turn it around.”

However, constantly fixing problems took its toll on him physically and mentally.

The obstacles continued to mount, and Effiong had a group of investors to report to weekly. The team had been shooting for over fifty days, and one-third of the crew members from Lagos had dropped out due to the exhausting nature of the shoot. Those who agreed to continue in Kaduna were running on fumes, drained by each gruelling day.

At this point of narrating the film’s journey, Effiong, who’s typically animated, first sounded sombre.

“Scale defeats people [and] it almost defeated me,” he recounted. Actually, it did! And motivation came from an unlikely source: a policeman.

On that particular day, the team, although depleted and knackered, had a major scene to shoot in Kaduna. It was an important explosion scene in the film, a set piece with a three million naira price tag. It had to be executed at a particular time, 6:45 P.M., to capture a certain atmospheric effect as the sun sets. They had one shot at it, as redoing the scene would cost time they didn't have and another three million naira they didn’t have.

However, the explosion failed!

The entire team was downcast; morale was already low and energy drained, but this just killed everyone. Effiong walked away speechless and overwhelmed with a sense of defeat. “I couldn’t face anyone,” he recalled. “I had failed everyone. I couldn't see past it. I hadn’t seen my family in God knows how long. I was tired and feeling alone.”

“This was the day I really did see Editi break down,” Enakarhire added. “This is someone who had carried us across the line many times. We were disappointed about the explosion, but the gravity of it didn’t hit us until we looked at Editi’s face, and he was shattered. He was speechless, really disappointed, and there was just silence on set; nobody knew what to say.”

In his emotional state, Effiong urged his team to leave without him because he didn’t want to get into the car with them. As they left, there was a security vehicle still on set.

“I got into the police car and didn’t look anyone in the eyes. I couldn't look anyone in the eyes. I was just sat there and looking at my shoes,” Effiong narrated. Then, unexpectedly, one of the policemen called unto him.

“Oga, let me tell you something,” the officer said to him in pidgin English. “In my fifty years in this world — don’t mind the age that I gave the police, that one na football age — I have never seen anything like the things I see since I started working here.

“Every morning, I see you working and talking to everybody, big person, small person. You greet everybody. If someone says this is the person running this whole thing, nobody will believe it. But I know [because of] how your people talk about you. Everybody in this place came because of you. So for me to see you like this, it means this failed explosion is really weighing on your mind, but [with] the way you do [things every] morning, I believe you can do this right.

“Just go and sleep, Oga. Don’t overthink it. Just go to bed. Tomorrow, we’ll come and carry you. We’ll do it again. We’ll see this thing to the end.”

Moved by the officer’s words, Effiong did as he had been advised. They drove him to his hotel, and he went straight to bed; he didn’t watch daily footage or review notes as usual. He slept.

The failure of the explosion meant the following day was pregnant with loads of work. It was a pivotal scene and had to be done, but now it had to be done alongside the other things scheduled for the day.

Enakarhire and Effiong's assistant, Paul Greene, were surprised to find him awake and ready for the day when they visited his hotel room the following morning. “But not only was I up, I had papers, my laptop, and all that shit. I’ve got plans for the entire day,” Effiong recalled. “[I told] Joshua, ‘You know what? Today, everything we're supposed to, we're going to do it. We're going to nail every single fucking thing we had to do.’ He’s like, what's the plan? I'm on board.”

The plan involved splitting the team into two groups, “Yinka likes to shoot everything” and takes his time, but the day required a different approach, and everyone rallied behind it. Remember, the explosion scene cost three million naira? No problem, Effiong would pay from his pocket.

Despite nursing an ankle injury he got while riding a bike some days back, he was shuttling two different sets with different teams and overseeing how things went.

At 6 P.M., there was a quick break, so everyone took a breather before the scene. This time, the team was working towards an even bigger explosion — a go-big or go-home moment.

And at 6:45 P.M., boom, the explosion went off without a hitch, and there was jubilation on set. The day was saved; that policeman was right that they would fix everything.

Around December 2021, after spending months holed up in an editing room in London, The Black Book’s editing was completed. The option for distribution that made the most sense was with a global streamer, as only deals with either Netflix or Amazon’s Prime Video would yield profit. Discussions were had with both streamers, but Netflix presented the most opportunities for the film to fly globally.

“The Black Book is the biggest thing created in this era of Nollywood, and it needed, I guess, to be seen [as] that,” Effiong mentioned while stating he is open to working with the other streamer in the future because he appreciates the investment both companies are making in the industry.

Theatrical distribution was never an option because it would be impossible to recoup money via that route, but back when they were raising money, streamers hadn't yet settled into the country enough to draw confidence. However, Effiong always believed they would be fine if the film was good enough and excellent technically.

“If we make a good enough picture, we're gonna sell it; we will not be short of buyers,” he said. “So the question then is, what do we do to ensure that it's a good picture? Raise enough money, get the right team behind you, and you gotta be mad to really fuck it up.”

💚

A masterfully crafted piece.

Well done, Daniel.

Editi is a genius.

Because true genius, is in never giving up.