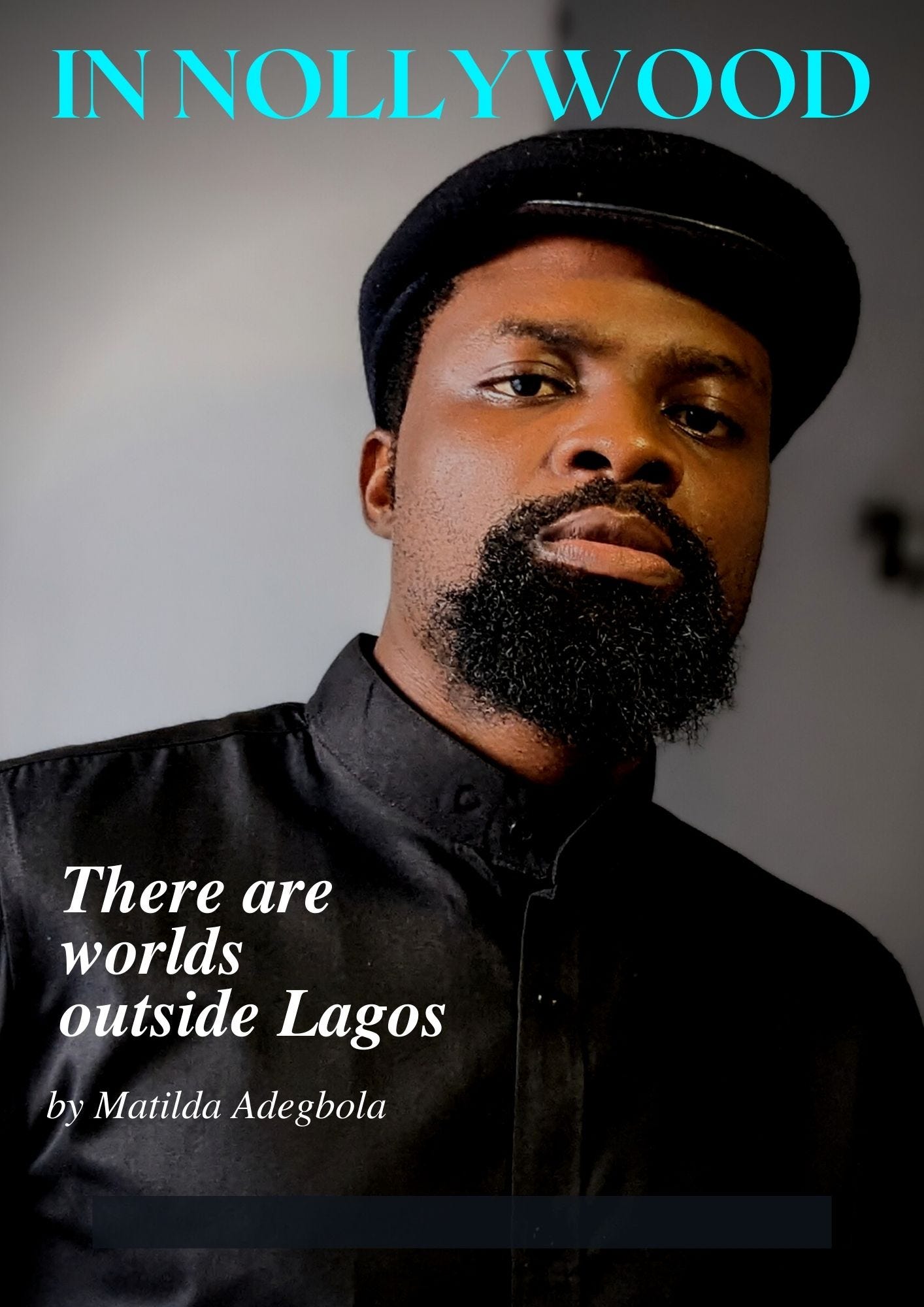

IN Conversation with Taiwo Egunjobi: “There are worlds outside Lagos.”

The 'In Ibadan' director talks about going to AFRIFF, his evolution as a filmmaker and the treasure trove that Ibadan is becoming for the Nigerian film industry.

As a filmmaker drawn to the worlds that raised him, Taiwo Egunjobi is keen on telling stories that touch on themes set within diverse backdrops of the city of Ibadan. His stories constantly circle back to the city, which informs a lot about how he sees the world. It is also because the director believes Ibadan, a historical city with obvious and hidden gems and uniquely stylistic architecture, has enormous potential to provide the Nigerian film industry with new and distinct stories.

“Breath of Life and Adire and more of the big films [this year] were shot in Ibadan,” the In Ibadan director tells In Nollywood. “Filmmakers and producers are realising that there are worlds that exist outside Lagos. They are interested in newer worlds and stories, so they are rediscovering Ibadan.”

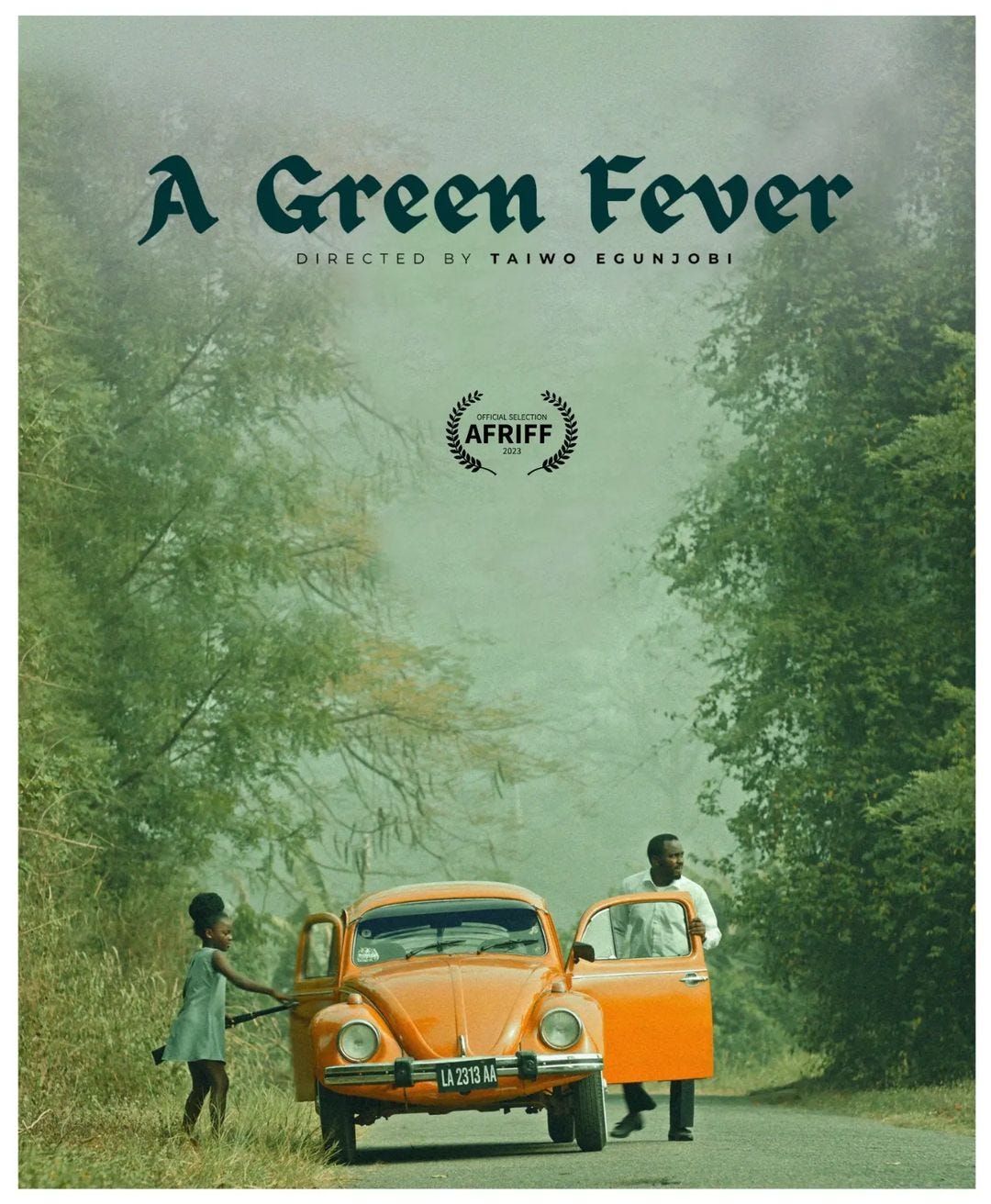

Growing up with his aged Professor father, who lived in the University of Ibadan (UI) staff quarters, meant that Egunjobi was constantly surrounded by storied materials that captured the 70s and 80s. These books, newspapers and other elements would become vital ingredients in curating the story world for A Green Fever, his third feature, a bottle film screened at the recently concluded African International Film Festival (AFRIFF) in Lagos.

The bottle film, set in a single location, follows a father who finds himself at the mercy of a ruthless Colonel while trying to save his daughter’s life. It is set against the backdrop of the '70s military regime — symbolised through the character of the arrogant and cynical Colonel Bashiru. Shot in Ibadan, like all Egunjobi films, the location is suitably adapted to the film’s idea of a colonial architecture, which is what the houses in UI’s staff quarters provide.

Certain traits were evident from this conversation about what set Egunjobi apart as a filmmaker. First is his commitment to innovation and reinvention. His growth can be seen in the progressive journey of his projects. This is more evident in his third feature, and he admits that every project has been more like film school for him.

In this conversation, Egunjobi talks about going to AFRIFF, the process and challenges of making the film, his evolution as a filmmaker and the treasure trove that Ibadan is becoming for the Nigerian film industry.

What did it feel like having your film screened at AFRIFF?

I was happy. Even more so because I had tried to get into it throughout my career, but I’d never been selected until now. I believe the festival is the biggest in Africa, and as such, it’s a platform I respect so much. So, being on AFRIFF shows that your work is respected and it’s a great avenue to meet cutting-edge filmmakers.

Why a bottle film?

There are obvious reasons and not-so-obvious ones. The obvious reason is that a bottle film is going to be logistically more comfortable to pull off. The not-so-obvious is that a bottle film is a creative challenge for me. It was a mix of these two reasons. I wanted to do a project that I could comfortably and logistically execute according to the available budget. Creatively, I’d wanted to execute a project with just two characters. I’ve been interested in this genre, so it was a case of my creativity meeting the perfect opportunity.

To piggyback on your reasons, why that specific location?

Anyone familiar with my work would see that I do a lot of my projects at UI. My dad was a professor, so I grew up a little bit in UI, and I like the school. I think it’s beautiful. One of the issues with making films in Nigeria is that our spaces are not always suitably designed architecturally. However, I found that UI offers you that. It offers calm and some planning, so it’s always a no-brainer for me. It’s also great that it offers the perfect location which suits the story I was going for in A Green Fever.

I have to say that this also affects the way I think about stories sometimes because when I start developing stories, the first thing I think about is the world of the story, and a lot of times, I like the world to be in a place around where I am. This is also because filmmaking is a logistical hell, so I like to fit myself into a space I can logistically pull off on a specific budget. That way, you can minimise the problems you’d encounter.

Do you find it a tad limiting that your mind circles back to almost the same location in your world-building?

I don’t think it’s limiting at all. Most of the filmmakers I respect and love like Yasujirō Ozu, Wes Anderson and the likes of Tarantino and Scorsese all have a body of work [with] themes connecting the films, and most times, it’s the spaces of these films. Though you may find differences and minor changes at the core, the world stays consistent. With Scorsese, you’d find that up till as recent as The Irishman, [it is] the world of gangs and you can tell that’s a world he grew up in.

So, for me, I find it even empowering because it’s the world I immediately relate to in terms of context and understanding the scenarios. My father was a very old man when he had us, and he raised me. I grew up around old books, old newspapers, and typewriters, so I love all of this stuff. It’s become natural to me. I worked with Tunde Kelani for a long time, and TK would always make a film around Yoruba culture based on where he was spiritually and psychologically. So, for me, it’s not at all limiting, and that doesn’t mean I cannot do projects outside the box. It just means my immediate contexts are reflected in these stories.

You talked earlier about giving yourself a creative challenge through this film. What were some of the challenges you encountered in shooting A Green Fever?

I have never even shared this before, but I had issues with locking down some locations with the University. My location manager botched the speed of the work, and this caused some issues with the authorities. There were times when some of my equipment was confiscated — I’ve not told anybody this — and we had to manage to continue shooting. There were even scenes in the film where we could only do one take. The first scene had to be gotten in one single take.

Though we eventually got back our equipment on the final day, we had to make do regardless. Some locations had to be changed. The main house itself was shot in three different locations, and making all of that fit seamlessly was serious work for various departments to keep the story flowing from a narrative point of view.

Another challenge was the regular challenge of when you begin to see actors perform and understand the story afresh with the new energy that actors bring to the table. That becomes a creative challenge but also exciting because you get to ask yourself how you can adapt to the new qualities you’re discovering about the characters that you didn’t write in the script but the actors are bringing. How do you adapt to make a better story? The temptation would be to hold on to the script and abandon the script you’re getting with the actors, but I decided to be flexible. It’s tasking mentally and emotionally, especially when you’re not shooting a film linearly, but thankfully, we were able to pull it off.

Speaking of actors bringing something new, I’d like to discuss Colonel Bashiru’s. I have to say William Benson embodied the role of an arrogant cynic. I’ve read about your fascination with the people and events of the ’70s and the ’80s, so I wondered if you based Bashiru on a specific persona. Also, what about Benson made you think he was perfect for the role?

I find that question quite intriguing. I had someone in mind when I was building that character, but I really would like to hear your thoughts, and I imagine you’d tell me later. But when we were writing this character, a character that was top of mind was Hans Landa in Inglourious Basterds.

I first saw Benson in Imoh Umoren’s The Herbert Macaulay Affair, a biopic of the man of the same name. Seeing him play that role told me how authentic he was as an actor, and then I saw he does a lot of theatre. I have respect for actors that have theatre training, and because what we were writing with A Green Fever was going to require some amount of theatrical training, in the sense that they have this hundred-page script that needed to be captured theatrically in that claustrophobic space where you were not cutting or it was just actors reliving lines. He was the only person on the list for the role and a lot of what the viewer sees are things he brought himself during the script reading after carefully studying and understanding the character himself.

One poignant quality of A Green Fever is the suspense. How were you able to effectively manage the suspense factor to ensure that the audience stays excited throughout the film?

As a filmmaker who wants to incorporate this in a bottle film, you owe it to yourself to study and research exhaustively the greats who have done these kinds of films. I’m talking about The Hateful Eight, Rear Window, and 12 Angry Men, and try to extract the different features to almost a scientific level. You have to understand the emotional gearing that is going on in the story. Though the premise of the story already packs a lot of suspense potential, at a very engineering level of the timing and preempting the emotional response of the audience and effectively managing the two. There’s no point in making a bottle film and boring your audience. It’s about working with an emotional map, raising the stakes where necessary and intensifying the heat when necessary.

It’s a lot of storytelling and instinctive work, but most of all, it’s also a lot of engineering where you break it into pieces and put it back together to maintain a constant stream of suspense, thrill, and excitement, which was what we were going for. So, finding the right authentic narrative tool was paramount.

How do you think you have evolved as a Filmmaker?

I started making films in 2013 with Martin Chukwu and the rest of the UI gang. I also grew up enjoying the films of Tunde Kelani before discovering the likes of Tarantino, Scorsese, and Wes Anderson. Then I started developing an aesthetic and doing short films like Amope. Later, I got a better feel of what I enjoyed when it came to the visual world of my film and the cinematographic language. I began to build a frame. Although I tilted a bit away from that frame with All Na Vibes, I discovered that the experience was good for me.

All the films I’ve done till now have been like attending film school for me. Now I know exactly what I want my camera language to be, the worlds I want my stories to be in, and the kinds of stories that intrigue me. I’ve directed my first and second films, and now, the third time, I’m assured as an artist to a certain degree: I have a clear artistic vision and understand exactly what I want to do.

What impact do you think shooting in your choice location is having on the industry and what hidden gems do you think this city possesses for filmmaking?

That’s one of the ways we’re growing as a film industry. A lot of films this year alone were done in Ibadan. We have been able to bring some of the most successful films out of Ibadan. Breath of Life and Adire and more big films were shot in Ibadan. Filmmakers and producers are realising that there are worlds that exist outside Lagos. They are interested in newer worlds and stories, so they are rediscovering Ibadan.

Furthermore, so many things about Ibadan are yet to be discovered. There are older buildings like the Bowers Towers, Mapo Hall, the old museum, and the Oyo town. All these locations still retain the characters of the 70s. These locations are opportunities for filmmakers to imagine their stories about Ibadan, which is fast becoming a destination location for films.

UI alone has seen two major TV productions this year. There is a visual renaissance around the city. There is a church, St. Peter's Anglican Church, a very beautiful location where I shot some scenes there even though I didn’t have to. There is the Chapel of Resurrection, which has a lot of modernist architecture. The Dominican University and New Culture Studios built by Dermas Nwoko. There are beautiful places that have retained their characters like Mokola and Apata. There are so many more locations that I would even refrain from giving out — just kidding — but Ibadan is a destination right now, and it’s being discovered again. It’s always been like this historically. Most film endeavours started in Ibadan in the 70s. There were cinemas — my Dad owned one then with a Lebanese man. Ibadan has a rich heritage in filmmaking, and I am happy we’re getting back to that time in the Nigerian film industry.

Lovely read