Is The Cinema Audience Avoiding Nollywood?

Nollywood’s market share in cinemas is at 25.8 per cent, down from the 39.3 per cent it held in the first half of 2021.

Nollywood’s market share in cinemas is at 25.8 per cent, down from the 39.3 per cent it held in the first half of 2021. This is despite the fact that in both years, total cinema admissions have remained at the same ballpoint of 1. 49 million with 7, 000 more admissions recorded in 2022.

Yet, the little increase in total admissions counted in favour of Hollywood titles leaving Nollywood films scrambling for an even smaller percentage of cinema-goers. The 2022 drop is an all-time low despite the industry's seemingly stable streak in the last five years. Year in, year out, the industry had flirted with about 40 per cent market share while a large chunk of the remaining 60 per cent was held by Hollywood.

"In the first half of 2022, just 25.8 per cent of the current cinema market share is held by Nollywood. "

As the industry recovered from the brutal pandemic lockdown in 2021, it still managed to snag about 39.3 per cent of the market share but surprisingly has failed to hold its own in 2022, with relaxed COVID restrictions and growing global attention.

In the first half of 2021, about 1,491,530 tickets were sold and Nollywood clinched 964,523. Meanwhile, out of the 1,498,934 tickets sold in the first half of 2022, Nollywood sold about 520,656, which is a 46 percent decrease from the previous year.

In 2021, titles like Omo Ghetto, Prophetess, Breaded Life and Ayinla danced with the audience in the cinemas before their eventual exits to streaming platforms. They held their own against films like The Hitman’s Bodyguard’s Wife, Godzilla vs Kong, and Fast and Furious 9 among other average Hollywood box office hits.

Nollywood Cinema Admissions (2021 vs 2022)

In 2022, ten Nollywood films opened the year struggling for space with Spiderman: No Way Home which was in its third week. They include Christmas in Miami, Superstar and Aki & PawPaw, all of which were among the top five. As usual, the first eight weeks of the year are spillover holiday films snatching the last bit of coins while new ones struggle to find a corner to cash in from. By February, Nollywood’s answer to Jennifer Lopez’s Marry Me was Before Valentine and Dinner at my Place which performed a little above average.

By the end of February 2022, about 181,576 cinema admissions were recorded, 47,413 of which went to Nollywood. In comparison, 186,128 tickets were sold in the same period in 2021 and 166,120 went to Nollywood. More films struggled to gross above N5 million in 2022 than they did in previous years. The slow upward climb for Nollywood films continued well until April when King of Thieves premiered. At the end of its first weekend, it raked in over N42 million; out of the 23, 846 people who watched Nollywood films that weekend, 20, 739 were in the cinemas for King of Thieves.

In May, whatever momentum the home film industry had gathered was overtaken by the entrance of Marvel’s Doctor Strange with 74,949 people going to see it in the first few days. June did not exactly fare better.

There are always about 10 Nollywood movies in the cinema, per time. While some movies such as Omo Ghetto (2021) have thousands of admissions, others get only about ten people weekly. Tickets range between N1,200 to N5, 000 depending on the buzz around the movie and the weekly performance. There have been unicorns of some sort in the two years.

Funke Akindele’s 'Omo’ defied expectations in 2021, when it grossed over N636 million before making it to a streaming platform. In 2022, Femi Adebayo’s 'King of Thieves ushered a new movement and made over N300 million in total cinema gross and is currently streaming on Amazon Prime.

Nollywood's decline in market share calls for some introspection and stakeholders are constantly debating several possibilities. But two questions have been on most minds — what is the role of streaming in this and what is the place of the cinema distributor?

What Is The Role Of Streaming Platforms In This?

(Distribution of High Engagement Nollywood Films Across Streaming Platforms)

The problem with Nollywood has remained the same – mostly hype over content leading to constant disappointment. With the introduction of streaming, it is cheaper to hedge all your Nollywood gamble on one platform, which costs less than N5, 000 monthly, than go through traffic and spend at least N2, 000 per film (outside other costs). The audience is afraid to keep gambling, and the economy does not make it easier to throw more money to the wind.

This is why when they find a film that is way less disappointing, they reward it with loyalty, hoping stakeholders in the industry will take hints. There are two issues here. The first is that general film admissions are not growing. For the last three years, except 2020, about 1.5 million tickets have been sold in the first half of each year. It is a stagnant number annually with slight variations in market shares between the players.

The second is the shrinking market share by Nollywood, which is alarming given that it defeats the multiple sources of income debate and further slows down the process of customer acquisition for films in Nigeria.

A Growing Trend In Film Watching Preference?

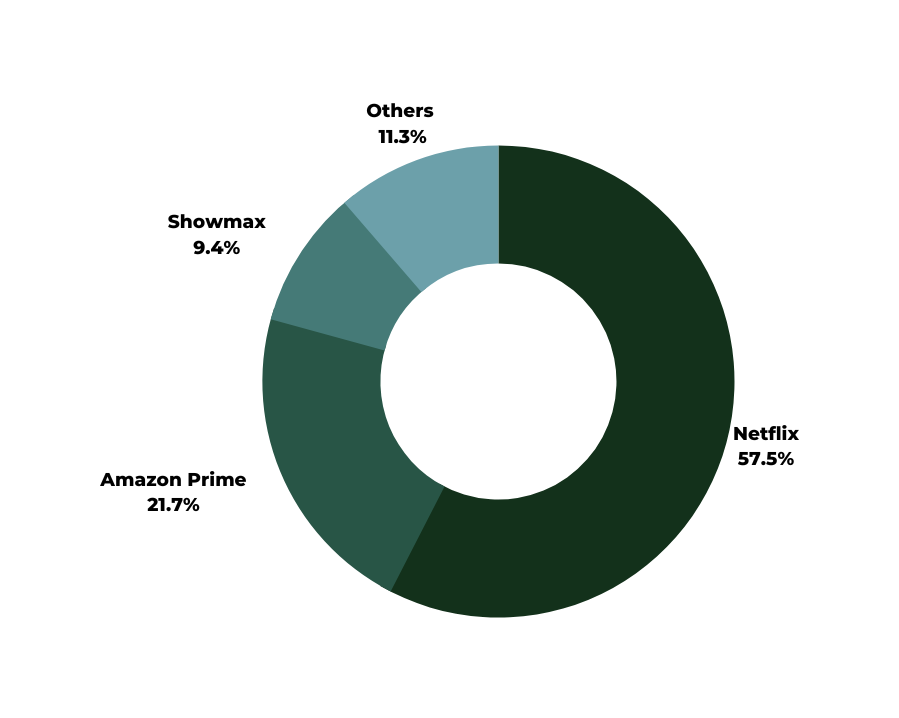

It is important to note that there are different sects of film audiences in Nigeria — the Asaba film audience, the cable TV audience, the cinema audience, the streaming audience (further divided into Netflix versus Amazon) and the web audience. Sometimes, these sects crisscross, but over the years, data has shown an increasing number of the web audience bingeing free web series and Asaba movies on YouTube. The other large chunk is for streaming and then cinema.

The rationale is simple. People will pick a free service first, then wisely choose a bundle paid-for service (in this case, Cable TV first, which has been around for a long time and remains a huge status symbol for a particular generation, then platforms like Netflix which allows password sharing and is a new pop culture reference for a much younger generation).

But before Netflix, Amazon and others, Nigerian films in the cinema got revamped PR with 'The Wedding Party' and an entire renaissance that piqued the audience's interest began. This soon plateaued and was exacerbated by recurring story and production problems in Nollywood films. Again, it is better to wait till they all get on a streaming platform (as they would, anyway) and watch there while one spends the cinema budget on Hollywood films, with overall better production value.

If the audience is beginning to depend more on streaming to see Nollywood films, the filmmakers and other stakeholders have a heavy hand in this. They created a system where films make their debut on the big screen and go on to stream on an online platform about three months later. To the audience, the wait is not an unbearably long one to watch a Nollywood film, especially if expectations are low.

There is nothing exactly wrong with this model as filmmakers need to hedge for better returns. However, this is the path for about 72 per cent of Nollywood films, regardless of their quality. It is almost as though the distributors, most of whom double as streaming aggregators, enjoy betting against themselves in the cinemas.

Have Distributors Given Up On Growing The Cinema Culture?

There is a slow disenchantment with the cinema distribution process. The primary reason is that the returns are not what they are hyped to be and secondly, they do not seem to be improving anytime soon.

Most of the filmmakers, emerging and established, who spoke with Inside Nollywood about the cinema distribution process decried the massive cuts — to the exhibitors, the distributors and taxes — that followed their decision to screen in the cinemas. They noted frankly that screening in the cinema is to gather clout so one can get a good streaming deal.

Filmmaking in Nigeria is tough and relatively expensive, hence the need to properly calculate the best route for quick and profitable returns. With the interconnectivity of the internet expanding every day, filmmakers are fast learning to research distribution and figure out ways to handle it themselves. In cases where they work with the distributors, they spread their deals as wide as possible to maximise returns.

The worry filmmakers have is further heightened by the disturbing data on the acceptance of Nollywood films at the box office. The drop from 40 per cent market share to 25.8 per cent is almost as disturbing as the realisation that the admission numbers have remained stagnant. This shows that cinema in Nigeria has reached its peak admissions while exhibitors/distributors are working towards expanding the market at a very slow pace.

Is The Hollywood-First Trend Working Out For Exhibitors?

While exhibitors and distributors should be worried, they appear to abandon filmmakers after the first week of their film’s release, hoping that the audience’s word of mouth and/or the filmmaker’s existing community would sell the film while they wait to pounce on a big chunk of the returns. It appears wiser to some filmmakers, especially those with clout, to sell to the highest streaming bidder to recoup investments and manage some profits rather than the uncertain hassle of the Nigerian box office.

A lot of the blame is constantly heaped at the foot of a growing streaming culture which is the global answer but the Nollywood film market, locally, is not ripe enough for this conversation. There is no strong baseline cinema culture to start with and measure against. Nigerians only actively began trying cinemas again less than nine years ago and the last decade did not exactly finish well.

The distributors appear to have done a poor job in strengthening the culture and actively developing the cinema into a complementary source of income rather than a competitive source, side by side with the streamers. Again, it is important to note that the top cinema distributors are also aggregators for streamers. Perhaps they have too much on their hands and have not figured out how to earn money as aggregators and improve the cinema culture. Before then, we wait for the next film(s) that will save the cinemas.

This article was originally published in The Industry.