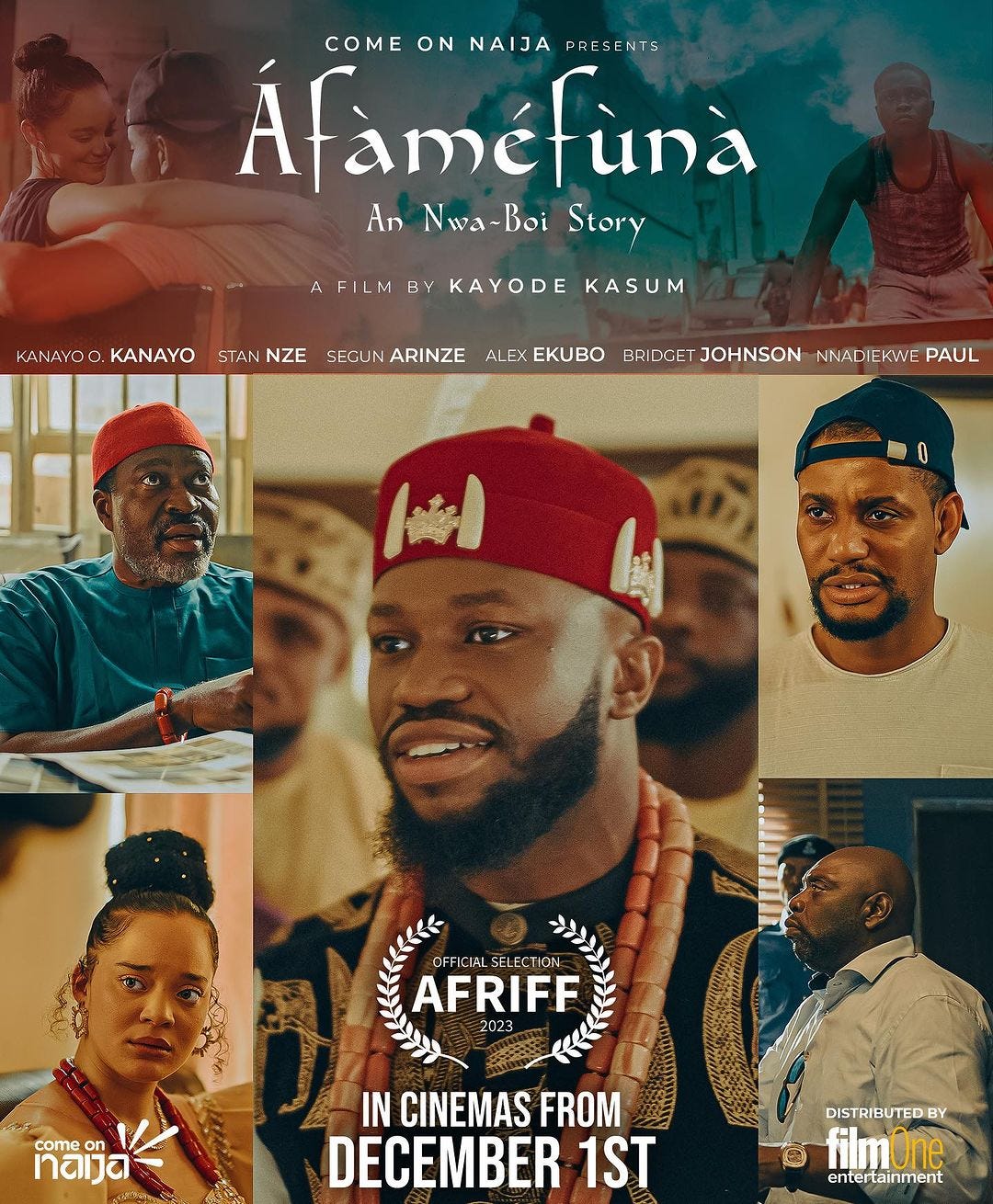

Kayode Kasum’s Sentimental and Culturally Triumphant ‘Afamefuna’

A compelling story that weaves culture and human complexities within the nwa boi system with a nuanced authenticity.

Igbo Amaka best describes Afamefuna, Kayode Kasum’s bittersweet love letter to the Igbo apprenticeship system. It is a compelling story that deftly weaves culture and human complexities within the nwa boi system with a nuanced authenticity unexpected from a non-Igbo filmmaker. But Kasum is a sentimental filmmaker who often approaches his stories with sincerity and humility; he cares deeply about emotions and wants you to feel things, and will therefore submit to the emotions and history of the story in front of him.

In an interview with In Nollywood, the filmmaker says, “I feel like films should be like big hugs, and I want the audience to feel when they see my films.” This is evident in Afamefuna, a big film that plucks at your heartstrings. Kasum's sentimentality manifests in several ways in this film. One of my favourites is a captivating monologue from Kanayo. O Kanayo. It’s a tribute to the resilient nature of the Igbo person, an acknowledgement of the war and what it did to us, and how we survived.

“The Igbo business empire is built on hard work and brotherhood,” Kanayo’s character, simply named Odogwu, narrates in Igbo. “The Igbo business collapsed after the war. Afamefuna, the war did something to us. War is bad.”

He was teaching his newest apprentice, the seventeen-year-old wide-eyed Afamefuna, about the business, the ethics of it, and also the sentimental and historical side. Afamefuna, played in his teens by the impressive Paul Nnadiekwe, is a boy from Onitsha whose mum has dropped with Odogwu to learn the business.

On his first day, he is introduced to Paulo, who has been with their master for a while and understands the market well. Paulo shows him around and grooms him on the art of sales as known by the Igbo trader. He also teaches him how to be cool, how to dress, the way to carry his bag, and how to relate with the different characters in the market. Basically, Afam was learning from their Oga, but Paulo did the watering.

So it would come as a rude shock years later when Odogwu decides that Afam, the junior apprentice, is more deserving of settlement while Paulo remains with him. To be fair, Afam deserves it. He has been a good servant — dutiful, inventive, and, most importantly, honest. Paulo hasn’t been sincere, and he’s doing shady stuff with the master’s daughter, Amaka — a belle played masterfully vulnerable as an adult by Atlanta Bridget Johnson. But overall, he’s been okay.

Paulo doesn’t take this well, which leads to friction between the two men, who are now practically brothers, even though Afam covets Amaka, who is Paulo’s girl.

Their disagreement takes the film on a different dimension and, in typical Kasum’s fashion, it morphs into a genre-bending story. This time, it’s well-oiled and comes together beautifully.

The manner in which Kasum, a Yoruba man, portrays the Igbo apprenticeship system is praiseworthy. People, including me, a fan of Kasum’s work, were worried. The Igbo people are very protective of our culture, and the worry was how a non-Igbo filmmaker — although working with a predominantly Igbo cast and an Igbo screenwriter, Anyanwu Sandra Adaora — would capture the fine points of the nwa boi system. But Kasum tells this story carefully and with empathy. The nuance of the Igbo apprenticeship system isn’t lost in the film. It’s about brotherhood, dignity in labour and resilience, and Kasum portrays all this with charm.

Even the dark side of this apprenticeship system, which can creep in due to greed and favouritism, is deftly portrayed.

The best scene occurs an hour or so into the film. It features two leading Nollywood men giving perhaps the best performances of their careers. The two men are Stan Eze and Alex Ekubo, and they are playing the adult Afamefuna and Paulo, respectively.

In the scene, Ekubo’s Paulo blackmails Nze’s Afam for taking what belongs to him, and even more from him.

What sets this scene apart is the dance between dialogue and camera — the staging of the switch in authority as both men go at each other and how both actors selflessly trust and commit to each other. When Paulo needs to be the powerful person in the frame, Nze submits to Ekubo. And vice versa. In one moment, Nze's voice roars and trembles after an important plot point triggers him, but Ekubo, though quieter and seated in that moment, is the more menacing presence. It is an excellent rendition of how actors can work a scene.

The scene, and this film in general, opens a new layer to Kasum’s directing. He’s always been great at the simple things, but he does the more intricate things exceptionally well here. He also finds a balance with his love for bending genres while marrying scale with intimacy. Afamefuna feels grand, maybe too long, and intimate.

With directing the actors, he’s remarkably excellent here. The film has the best Kanayo Kanayo performance in recent years and the best Alex Ekubo performance I have seen. Ekubo relishes every single moment he gets to be diabolical, but it's not the showy type of performance; it is the menacing type that’s quiet but assured and unforgettable.

Another terrific actor here is Johnson, who plays the adult Amaka. Every scene she appears in reminds one of how alluring and magnetic a performance can be when a gifted actor is in the frame. Her body concocts a wave of reactions when she deals with the inner conflict her character battles. A terribly good cry is a lost art in today’s Nollywood, where actors often cover their faces or turn away, afraid of their own ability to show devastating vulnerability in front of a camera, but Johnson embraces it. She cries with a red face, trembling hands and shaky voice but also a look that’s searching for answers within.

The gift here is that her character, although on the fringes for most of the film, is one of the better-written ones in Adaora’s simple screenplay and plays a central role in the film’s dramatic core — the relationship between Paulo and Afamefuna and Odogwu. All her life deceived and then heartbroken by her father’s boy whom she loves; meanwhile, the man who truly deserves her and cares for her is waiting by the side. But because life is twisted, a cursed seed is planted just before she finds true happiness — that sort of arc is a gift for an actor who’s ready.

I enjoyed this review. Well done.