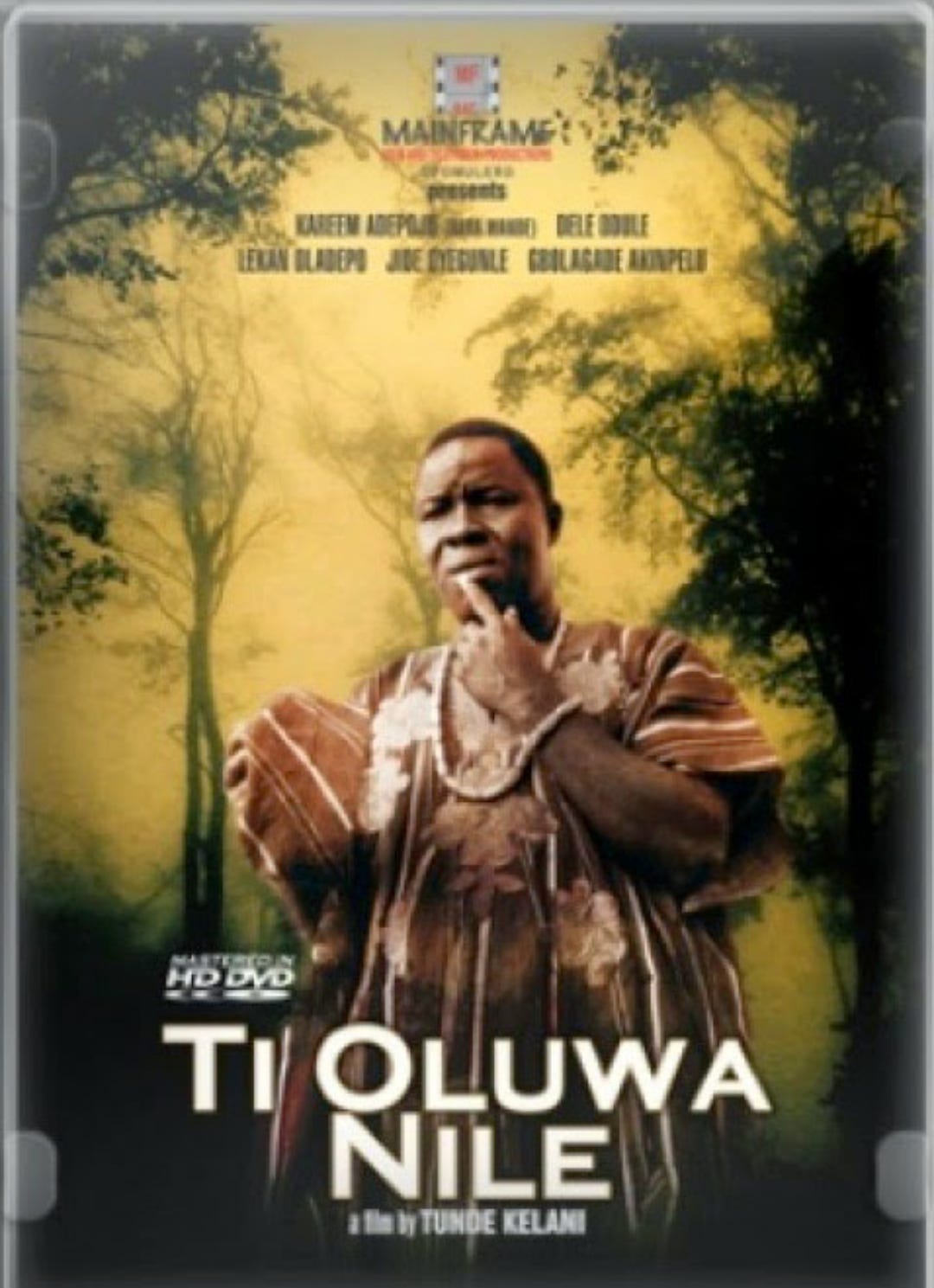

Retro Nolly: Tunde Kelani’s 'Ti Oluwa Ni Ile' is a Conflict of Ideas and Worldviews.

Tunde Kelani's Ti Oluwa Ni Ile follows two businessmen who engage the service of a corrupt and ambitious village chief, to sell an ancestral land.

Retro Nolly is a weekly series of retrospective reviews of classic Nollywood films by Seyi Lasisi. We will be looking at these films with modern eyes, dissecting what made them unique and how they speak to today’s filmmaking, culture and society.

Ti Oluwa Ni Ile, translated as The Land is the Lord’s, revolves around the story of two businessmen who engage the service of a corrupt and ambitious village chief, played by Kareem “Baba Wande'' Adepoju, to sell one of the village's ancestral lands. Propelled by the exorbitant kickback the deal holds, the chief enlists the help of a struggling community lawyer with an ambition to live a comforting life; together, the duo scheme and act out legal plans leading to the sale of the land to the businessmen.

Credited as Tunde Kelani’s directorial debut, Ti Oluwa Ni Ile, written by Baba Wande, sets itself apart not only for its social commentary or didactic tone, but as a film that tackles the question of environmental well-being and protection of the cultural and architectural ecosystem in the face of crushing modernity. Representing the annihilating modernity are the businessmen, who recognise the economic value of the land, and aiding their activities are the village chief and the lawyer. Fighting for the preservation of the ancestral land are the villagers and King, who is familiar with the cultural value of the land.

The film doesn't progressively play out as being overtly philosophical or cerebral, but as the King and the lawyer and desirous chief engage in a legal battle to contend the rightful owner of the land, we are watching not two opposing forces, but witnessing men, who due to their conflicting interests, represent conflicting philosophies and worldviews.

The legal suit that ensued in a bid to secure the land from the preying businessmen points to an important conversation about the need for written documentation. The King’s and the village council's reliance on memory and word-of-mouth testimony shows a society slowly trailing the modern world and heightens the need for documentation. These written documents serve as a credible reference and testimony when auditory evidence, internalised history, and custodian of history are extinct or lacking. One can metaphorically extend the meaning of this part of the film in addressing the question of historical and cultural amnesia prevalent in Africa. The concerted imperialist effort of the colonial master, in plunging, stealing, and describing African culture as barbaric, resulted in generational amnesia. With scanty archival materials, totems and the absence of historians, it's mentally impossible to lay claim to our history as a people.

Another important aspect of the film is how it captures modern-day reality despite being produced in 1993. The desecration of historical places and the selling of monuments to give way for recreational centres has led to the paucity of cultural artefacts and totems of cultural identity. Representing the village chief and lawyer are modern-day politicians and government officials who sell off locations of cultural and historical value for personal benefits.

Ti Oluwa Nile is one of my favourite films to watch. Since I first saw it in the 90s at Ile-Ife on VHS, I continue to find new ways to reflect on this sprawling saga that extends through three parts, released in an untimely fashion through the early 90s. It follows the story of a high chief Asiyanbi, played to perfection by Baba Wande, who also wrote the screenplay. It was Tunde Kelani's first feature as a director (prior to this he was better known as a DOP and director of music videos) and arguably his best. Some say his best films are his treatment of modern middleclass families.I disagree, his earthier films, closer to indigenous Yoruba traditions are his best works. Of course, only after excluding the punishingly didactic sequel to his classic, Saworoide, Agogo Eewo. That Baba Wande continues to feel cheated in terms of royalties for this film is a sore thumb. Incidentally, before happening on this essay, I watched a video interview where Baba Wande spoke about his close friendship to Kelani prior to making the film. Kelani invited him to submit a script for his new production company. Baba Wande brought his gravitas as an thespian in recruiting actors alongside providing the script. Kelani bankrolled the production. For Baba Wande, they began with love, without which they may not have begun, even if it ended in disrepute. Baba Wande has not starred in any other Kelani films, if I remember correctly. But Ti Oluwanile remains a lifetime performance. It sits between the Travelling theatre Yoruba tradition and the possibilities of Home Video. Expansively elaborate in its ambition and story-telling, it attempts an odyssey with episodic distractions. The portal may be the trickery of fraudulent sale of ancestral land, but the story goes over and beyond this. It deals with land, love, sex, social status, tradition, religion. Even the handling of the dead is dealt with humorously. Once Asiyanbi deduces that the burial of his co-conspirator marks him as the next target for a mysterious death, he brings every weapon in his arsenal to fight for his life. At every instance of temporary reprieve, our anti-hero strikes again, revealing another layer to his weakness and vanities: the love of money, status and good life. Although the film weakens as the plot progressed and the handling of time could have been economical but such small sins can be forgiven. Thank you Seyi.